- Home

- Dave Dewitt

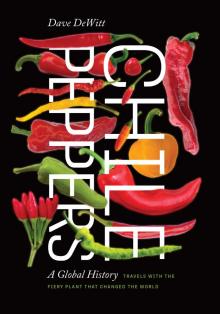

Chile Peppers Page 26

Chile Peppers Read online

Page 26

½

teaspoon ground turmeric

½

teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

½

teaspoon ground nutmeg

½

teaspoon ground cinnamon

¼

teaspoon ground cumin

¼

teaspoon ground cloves

½

teaspoon salt

Line a strainer with a dampened cheesecloth, add the yogurt, and place over a bowl. Put the bowl and strainer in the refrigerator, and let the yogurt drain for 4 hours to thicken.

Make slashes in the chicken about 2 inches deep. Combine the cayenne, paprika, and black pepper, and rub the mixture into slashes. Add the lemon juice and coat the chicken. Marinate the chicken for 30 minutes at room temperature, then drain.

Put the drained yogurt and all the rest of the ingredients for the marinade in a blender or food processor and puree until smooth. Pour the marinade over the chicken and, using your fingers, rub it into the meat. Cover the chicken and refrigerate for 24 hours, turning at least once.

Start a charcoal or hardwood fire in your barbecue. Place the grill 2 inches over the coals and grill the chicken for 10 minutes, turning once. Use the marinade to baste the chicken as it cooks. Raise the grill to 5 inches and continue cooking for another 5 minutes, turning once.

Remove the chicken and brush with the melted butter. Return the chicken to the grill and continue to cook for another 5 minutes, turning once, until the chicken is done and the juices run clear.

Serve the chicken garnished with lemon slices and with the mint raita on the side.

PAKORAS SHIKARBADI-STYLE

yield

6 servings

heat scale

mild

These are some of the easiest Indian snacks to make. You can use any vegetable you like, but we recommend the softer vegetables such as pepper, eggplant, onion, and thinly sliced potato.

2

cups gram (chickpea) flour

1

teaspoon red chile powder

1

teaspoon salt

1

teaspoon turmeric

1

teaspoon baking powder

Water

Peanut oil for frying

Thinly sliced green chiles, onions, eggplant, and potatoes

In a bowl, combine the gram flour, chile powder, salt, turmeric, and baking powder, and mix well. Add water and mix well until the batter has a creamy consistency. Heat the oil in a deep pan until water splatters when sprinkled on it. Dip the vegetables in the batter, drop them in the oil a few at a time, and cook them until they are golden brown.

SANJAY’S JEERA CHICKEN

yield

8 servings

heat scale

varies

A high-heat source is essential for this dish. It was cooked for us outdoors over a large gas flame and consequently took only a few minutes to prepare. It is usually served over plain white rice. Sanjay says this chicken tastes better if the bones are left in. He also says that chileheads are permitted to add red chile powder.

1

cup water

1

pound butter

2

chickens, skin removed, chopped into 3-inch pieces

1

tablespoon salt

3

tablespoons ground jeera (cumin)

1

teaspoon cumin seeds

3

tablespoons ground black pepper

1

tablespoon red chile powder (optional)

In a large pot, heat the water to boiling, then add the butter. When the butter is melted and well mixed with the water, add the chicken and salt. Stir for 2 to 3 minutes over high heat. Then add the ground cumin, whole cumin seeds, black pepper, and red chile, if using, and continue stirring and cooking for about 20 to 25 minutes over high heat. The sauce needs to be almost a paste, and the chicken is usually done when the butter returns to the top of the paste. Cut a piece of chicken open to make sure that all the pink is gone from the meat.

Fire in the wok: cooking in a Singapore hawker center. Photograph by Rick Browne. Used with permission.

eight

RECORD HEAT IN ASIA

Oh soul, come back! Why should you go so far away?

All your household have come to do you honor:

All kinds of good food are ready:

Bitter, salt, sour, hot, and sweet:

There are dishes of all flavors.

Chao Hun, ca. 200 BC

This ancient poem predicts the use of chile peppers in China 20 centuries before they arrived there. It is a fragment from “The Summons of the Soul,” written in the third century BC by the Chinese poet Chao Hun, which illustrates an ideal of Asian cookery that persists to this day: the merging of all possible taste sensations into a single dish, or over the course of the meal. Although the poem establishes the necessity of hot spices in Asian cooking, there was one slight problem: chile peppers did not exist in Asia at that time, so the “hot” flavors of good food could not be fully accomplished.

What spice fired up Asian cooking before chiles arrived on the scene? Most probably, the fruit of a thorny shrub called Fagara, also known as prickly ash. The berries of this bush are called brown pepper or Sichuan pepper and are pungent in a manner similar to peppercorns, ginger, or horseradish but are not truly hot like chiles. They tend to numb the mouth. Yes, they assault the senses momentarily, but then quickly fade away because they lack the real burn of capsaicin. Alas Fagara was a modest flame compared to what was on the way.

Asians waited 2,000 years for a truly hot ingredient to complement their other classic flavors and to fulfill the prophecy of Chao Hun’s poem. They were finally rewarded in the sixteenth century, when the real heat arrived: chile peppers. Asian cuisines would never lack for heat again.

As often happens during the transfer of foods around the world, the New World origin of chile peppers is unknown or forgotten. European explorers and colonists assumed the plants were native to Africa or India because the natives they encountered so loved the hot fruits. In effect, chiles spread across the globe faster than history could keep track of them. The reason for this quick dissemination of chiles was simple: supply and demand. The traders and their customers simply loved the new hot spice.

Thai bird peppers. Photograph by P. D. Miller. Wikimedia. This work has been released into the public domain by its author.

Portuguese traders introduced the capsicums into Thailand as early as 1511, probably from their trading base in Malacca, between the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra. Although hard evidence is lacking, ethnobotanists theorize that Arab and Hindu traders carried the Indian chile peppers to Indonesia around the late 1520s, and from there to New Guinea. In 1529, a treaty between Spain and Portugal gave the Spanish control of the Philippines and the Portuguese control of Malaysia. By 1550, chiles had become well established in the East Indies, probably spread both by birds as well as by human trade and cultivation.

Some theories hold that either Malay, Chinese, or Portuguese traders first introduced chiles to China through the ports of Macao and Singapore, although other scenarios suggest that the chiles in western China were imported from India. The expansion of chile agriculture into Asia was assisted by the Spanish, who had colonies in the Philippines by 1571, and had established trade routes to Canton, China, and Nagasaki, Japan.

From Manila in the Philippines, the Spanish established a galleon route to Acapulco, Mexico, by way of Micronesia and Melanesia, thus spreading chile peppers into the Pacific Islands. So by 1593, just a century after Columbus “discovered” them and brought them back across the Atlantic, chile peppers had encircled the globe. It is an ironic culinary fact that the imported chiles became more important than many traditional spices in Asian cuisines, thus illustrating how the pungency of chiles has combined with other flavors to win a fanatic following of devotees.

Although chile pepper

s are present to some extent in all Asian countries, they are particularly beloved in the cuisines of three distinct regions: Thailand and nearby Laos and Vietnam; Indonesia and Malaysia; and China and Korea. Chile peppers do appear as condiments and occasionally in recipes from the Philippines and Japan, but they are less of a factor in those cuisines.

THE FIERY TRIANGLE: THAILAND AND ITS NEIGHBORS

The San Francisco Bay Area, with a total Thai population of about 1,000, has more than 100 Thai restaurants. The Los Angeles area, with fewer citizens of Thai heritage, has more than 200 Thai restaurants! It is for good reason that Thai cuisine has become a favorite of American fiery-food aficionados—it is one of the hottest cuisines in the world, and also one of the most diverse in terms of the different varieties of chiles that are used. As Thai-food expert Jennifer Brennan describes the process, chile peppers were “adopted by the Thai with a fervor normally associated with the return of a long-lost child.”

Perhaps, then, it is no surprise that Bangkok is also in the running for the title of hottest city in the world. This city is populated not only by the chile-loving Thais and Chinese but also by other ethnic groups that use them heavily in their cuisines: East Indians, Pakistanis, and Malays. Bangkok markets rival those of Mexico for the varieties of chiles (called prik) that are offered for sale. One of the most common chiles, prik chee fa, is fat and about four inches long and closely resembles a small version of the New Mexican pods. According to one source, the favorite chile of Thailand is prik kee nu luang, a small orange variety. Other chiles include a wax-type chile; the long, thin “Thai” chiles; cayenne or piquin varieties such as Thai bird pepper and the Japanese santaka; and Kashmiri chiles, which are close relatives of the jalapeños and serranos.

Chiles in the wholesale market, Bangkok. Photograph by Dave DeWitt.

Thai carved vegetables. Photograph by Dave DeWitt.

Kaeng phet mu (Thai red curry with pork). Photograph by Takeaway. Wikimedia. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The Kashmiri chiles are also called sriracha chiles. They are so named because a sauce made from these chiles originated in the Thai seaside town of Sriracha as an accompaniment to fish, and it became so popular that it has been bottled and sold around the world.

Another popular Thai sauce is nam prik, which consists of a bewildering number of possible ingredients including fish sauce, chiles, garlic, sugar, lime juice, and even egg yolks. The same traders who brought the chile pepper to Thailand also spread the use of curries from India to all parts of the globe. Consequently, Thailand is a perfect example of a culinary collision of cultures; Indian curry spices were combined with the latest exotic import—chile peppers—to create some of the hottest curries on earth. In fact, hot curries are staples in Thai cooking and take several forms. One form is curry pastes, which consist of onions, garlic, chiles, and curry spices such as coriander and cardamom all pounded together with mortar and pestle until smooth. Commercially prepared curry pastes can be purchased in Asian markets or made at home by utilizing a food processor or blender.

Another type of curry, kaeng, is a term for a bewildering variety of Thai curries. Some kaengs resemble liquid Indian curry sauces and are abundant with traditional curry spices such as turmeric, coriander, and cardamom. Another type of kaeng curry omits these curry spices and substitutes herbs like cilantro, but the chiles are still there. This second group of kaeng curries is said to be the original Thai curries, invented long before they were influenced by Indian spices. As with the curries of Sri Lanka, these kaeng curries are multicolored; depending on the color of the chiles and other spices, and the amount of coconut milk added, they range from light yellow to green to pale red.

Kaeng kari is yellow colored because it contains most of the curry spices, including turmeric, and is fairly mild. One of the more pungent of these kaeng curries, kaeng phet, is made with tiny red chiles, coconut milk, and basil leaves, and it is served with seafood.

Such a culinary practice illustrates yet another aspect of Thai cuisine: the presentation of the meal. “The Thais are as interested in beautiful presentation as the Japanese are,” writes Jennifer Brennan. “The contrasts of color and texture, of hot and cold, of spicy and mild, are as important here as in any cuisine in the world.”

Considering the emphasis on both heat and presentation in their cuisine, it is not surprising that the Thais love to garnish their hot meals with—what else?—hot chiles. Their adoration for the chile pepper extends to elaborately carved chile-pod flowers. They use multicolored small chiles for the best flower effect, with colors ranging from green to yellow to red to purple. The procedure for creating chile pepper–pod flowers is quite simple. Hold the chile by the stem on a cutting board and use a sharp knife to slice the chile in half, lengthwise, starting an eighth of an inch from the stem and moving down to the point (or apex, for the botanically minded). Rotate the chile 180 degrees and repeat the procedure until the chile is divided into sixteenths or more.

The thinner the “petals,” the more convincing the chiles will be as flowers when the chiles are soaked in water containing ice cubes, which is the next step. Immerse the chiles in ice water until the slices curl—a few hours—and then remove the seeds with the tip of a knife. The chile flowers are then arranged artistically on the platter and later devoured as a spicy salad condiment that accompanies the traditional Thai curries.

Vietnamese nuac cham sauce. Photograph by Guilhem Vellut. Wikipedia. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

The influence of such curries, with all their multiple spices, did not extend into Laos, which borders Thailand to the northeast. Rather, fresh small red and green chiles are used extensively in a number of chile pastes there. Jalapeño- and serrano-type chiles are beaten with pestles in huge mortars, and locally available spices are added. My favorite Laotian creation is a dish called mawk mak pbet, which is a delicious example of a fresh-chile recipe from that country. It features poblano or New Mexican chiles that are stuffed with vegetables, spices, and white fish, and then steamed.

Fish combined with chiles also provides the essential flavor of the third country of our “fiery triangle.” In Vietnam, where the heart of the chile cuisine coincides with the center of the country, principally in the city of Hue, a fish and chile sauce called nuac cham reigns supreme. It consists of fish sauce, lime, sugar, garlic, and fresh small red serrano-type chiles.

THE SPICIEST ISLANDS: INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, AND SINGAPORE

The spice trade was one of the primary motivating factors in European exploration of the rest of the world, so it is not surprising that many countries sought to control the output of the “Spice Islands.” These islands, which now comprise parts of the countries of Indonesia and Malaysia, produced cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, black pepper, and many other spices. What is surprising about the Spice Islands is that they were infiltrated and “conquered” by a New World spice—chile peppers.

After the Portuguese won control of the Strait of Malacca in 1511, it is probable that chile peppers were imported soon afterward by traders sailing to and from the Portuguese colony of Goa, India. Asian food authority Copeland Marks observes that the cuisine of the region would be “unthinkable without them. . . . When the chile arrived in Indonesia it was welcomed enthusiastically and now may be considered an addiction.”

In Indonesia, where chiles are variously called cabe or lombok, they are added to many dishes and often combined with coconut cream or milk. On the island of Java, sugar is added, making that cuisine a mixture of sweet, sour, and fiery hot. Some cooks there believe that the addition of sugar keeps the power of the chiles and other spices under control.

Indonesian sambal terasi that is served with raw vegetables (labab). Photograph by Gunawan Kartapranata. Wikimedia. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Perhaps the principal use of chiles in this part of Asia is in sauces that are spread over rice or are used as a dip for satay, barbecued

small chunks of meat. Chiles are often combined with peanuts for the satay dips. Other favorite hot-chile sauces are the sambals, which are relishes made from lime juice, shallots or onions, garlic, and fresh chiles, and are usually served over plain white rice. An Indonesian legend holds that even a plain-looking girl will find a husband if she can create a great sambal. On the island of Sumatra, cooks make lado—a sambal consisting of chiles, salt, tamarind, and shallots—which is stir-fried with seafood, hardboiled eggs, or vegetables.

One of the most interesting chile cuisines of Asia is the Nonya cooking of Singapore, which illustrates the collision of Chinese dishes with Malay spices such as curries and chiles. The Nonyas are descendants of mixed marriages of Malay women and Chinese men, who insisted that their wives cook in the Chinese style. The necessity of using Malaysian rather than Chinese produce resulted in the addition of chile peppers to the recipes.

A Singapore Fling

In 1992, people laughed in disbelief when we told them we were going to Singapore on business. “Yeah, right,” said one skeptic, “you foodies will use any excuse for a gourmet holiday.” But we were telling the truth. In fact, we took along our bathing suits on the trip but were so busy we never got to wear them.

Of course, we did dine out a bit—after all, it was our job. We were in Singapore to plan a culinary tour for the following year. Besides myself, along for the feast were my wife, Mary Jane Wilan, Ellie Leavitt of Rio Grande Travel, and her daughter, Laura Brancato.

Chile Peppers

Chile Peppers